A Gentle Introduction to the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT)

As we stand on the brink of the quantum computing era, the race is on to develop new cryptographic methods that can withstand attacks from both classical and quantum computers. At the heart of many of these next-generation, post-quantum cryptographic (PQC) schemes lies a powerful mathematical tool: the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT).

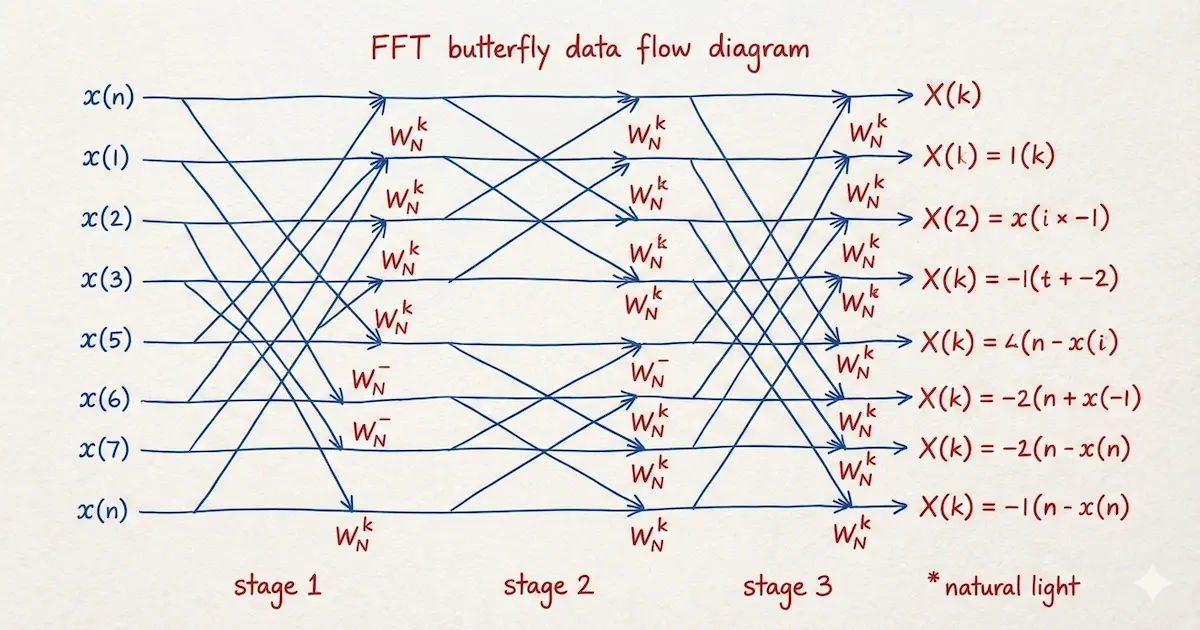

If you’re familiar with signal processing, you might have heard of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), an algorithm famous for its ability to efficiently analyze frequencies in signals. The NTT is essentially the FFT’s cousin, but adapted to work with integers in finite fields—a perfect fit for the world of cryptography.

The Problem with FFT in Cryptography

The standard Fast Fourier Transform is a brilliant algorithm for multiplying large polynomials quickly. It works by converting polynomials into a point-value representation, multiplying the points, and then converting back. However, it has a critical flaw for cryptographic applications: it relies on complex numbers, which are represented as floating-point numbers in computers.

Floating-point arithmetic involves rounding, leading to small precision errors. In cryptography, there is no room for error; a single bit difference can cascade into a completely invalid result. We need absolute precision.

Enter NTT: The Integer-Based Solution

The Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) solves the precision problem by swapping the world of complex numbers for the world of modular arithmetic. Instead of operating on an infinite field of complex numbers, the NTT operates on a finite field of integers modulo a prime number .

This has two key advantages:

- No Floating-Point Errors: All calculations are done with integers, ensuring perfect precision.

- Efficiency: The calculations remain incredibly fast, inheriting the speed of the FFT algorithm.

The magic ingredient that makes this work is finding an integer equivalent of the “primitive root of unity” used in the FFT. In the NTT, we find a special integer (omega) in our finite field that behaves just like its complex counterpart, allowing us to perform the transform and its inverse.

A Step-by-Step Walkthrough

Let’s walk through a concrete example of multiplying two polynomials using the NTT. We will calculate the product of and .

1. Setup

We need to choose our parameters:

- Modulus (): 17. We will work in the field of integers modulo 17.

- Transform Size (): 4. The product of two degree-1 polynomials has degree 2. To avoid aliasing, must be a power of 2 greater than 2. We pad our coefficient vectors with zeros to length 4.

- Root of Unity (): 13. We need an element such that . , , , .

- Inverse of (): 13. Since , the modular inverse of 4 is 13.

Our input vectors are:

- (representing )

- (representing )

2. Forward NTT

We transform vector into point-value form using the formula .

Similarly for vector :

3. Point-wise Multiplication

We multiply the transformed vectors element-by-element modulo 17 to get .

4. Inverse NTT (INTT)

Now we transform back to coefficients using the inverse formula. We use (since ) and multiply the final result by .

First, let’s compute the summation :

Finally, multiply by :

The result is , which corresponds to the polynomial . Matches the standard multiplication: .

The NTT and INTT Algorithms

For those who want a deeper look, let’s examine the forward and inverse transforms. The NTT takes a polynomial’s coefficient vector and transforms it into a point-value representation . The INTT reverses this process.

The forward NTT is defined as:

And the Inverse NTT is defined as:

Where:

- is the input vector of coefficients.

- is the transformed output vector.

- is the prime modulus.

- is the transform size (and a power of 2).

- is a primitive -th root of unity modulo .

- is the modular multiplicative inverse of modulo .

Here is an illustrative Python implementation of the NTT, which is analogous to the Cooley-Tukey FFT algorithm.

def ntt(a, N, w, n):

"""Number Theoretic Transform"""

# 1. Bit-reversal permutation

A = list(a)

for i in range(n):

rev_i = int(f'{i:0{n.bit_length()-1}b}'[::-1], 2)

if i < rev_i:

A[i], A[rev_i] = A[rev_i], A[i]

# 2. Butterfly operations

s = 1

while (m := 2**s) <= n:

w_m = pow(w, n // m, N)

for k in range(0, n, m):

w_pow = 1

for j in range(m // 2):

u = A[k + j]

t = (A[k + j + m // 2] * w_pow) % N

A[k + j] = (u + t) % N

A[k + j + m // 2] = (u - t + N) % N

w_pow = (w_pow * w_m) % N

s += 1

return AAnd here is the Python code for the Inverse NTT. Notice it’s nearly identical, just using the inverse root of unity and scaling the final result.

def intt(A, N, w_inv, n):

"""Inverse Number Theoretic Transform"""

# The INTT algorithm is the same as NTT, just with the inverse root

a = ntt(A, N, w_inv, n)

# Scale the result by n_inv

n_inv = pow(n, N - 2, N)

for i in range(n):

a[i] = (a[i] * n_inv) % N

return aThe bit-reversal step is a pre-processing permutation that reorders the input array to be in the correct order for the iterative butterfly operations that follow. This reordering is what allows the algorithm to be so efficient.

Beyond the Standard NTT: Variants and Cousins

While the standard Number Theoretic Transform is the workhorse of modern cryptography, it is part of a larger family of transforms, each optimized for specific constraints or mathematical structures.

- Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT): The grandfather of them all. While NTT operates on finite fields of integers, DFT operates on the field of complex numbers. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is simply an efficient algorithm to compute the DFT.

- Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT): A close relative of the DFT that uses only real numbers and cosine functions. It is best known for its “energy compaction” properties in signal processing (powering JPEG and MP3), but number-theoretic variants also exist for specialized integer arithmetic applications.

- Discrete Galois Transform (DGT): A specialized variant that operates over Galois extensions of finite fields (e.g., Gaussian integers modulo ). It effectively packs more information into each element, potentially halving the transform length required for a given polynomial degree. This is particularly relevant in optimizing post-quantum schemes like Kyber.

- Discrete Weighted Transform (DWT): A variation that applies weight factors to the input and output vectors. This is often used to perform “negacyclic” convolutions (common in lattice cryptography) or to compute linear convolutions without the full zero-padding overhead required by the standard cyclic convolution.

- Walsh-Hadamard Transform (WHT): A simplified transform that uses only additions and subtractions (no multiplications). While less powerful for general convolution than NTT/FFT, its speed makes it valuable in quantum algorithms, error-correcting codes, and specific cryptographic booleans.

- Irrational Base Discrete Weighted Transform (IBDWT): A flavor of DWT used in computations involving massive numbers (such as the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search). It allows for efficient multiplication using floating-point hardware while maintaining exact integer results through careful error analysis.

Quick Comparison

| Transform | Domain | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT/FFT | Complex Numbers | Signal Processing, Audio/Image | Mature hardware support, intuitive frequency analysis. |

| NTT | Finite Fields (Integers) | Cryptography, Large Integer Arithmetic | Exact precision (no rounding errors), efficient modulo operations. |

| DCT | Real Numbers | Compression (JPEG/MP3) | Energy compaction, real-valued (no complex storage). |

| DGT | Galois Extensions | Advanced PQC (e.g., Kyber) | Reduced transform length, higher information density. |

| DWT | Weighted Rings | Lattice Crypto, Huge Multiplications | Efficient negacyclic convolutions, reduced padding overhead. |

| WHT | Binary/Integers | Quantum Algo, Error Correction | Extremely fast (no multiplications required). |

Why is NTT a Game-Changer for Cryptography?

The primary application of NTT in cryptography is to perform fast polynomial multiplication. Many modern cryptographic schemes, especially those based on lattices, are built on operations involving very large polynomials.

Doing this multiplication naively would be too slow to be practical. The NTT provides a massive speedup, making these advanced cryptographic schemes feasible.

You can find NTTs at the core of the algorithms selected by NIST for post-quantum standardization, including:

- CRYSTALS-Kyber: A key-exchange mechanism designed to replace methods like Diffie-Hellman.

- CRYSTALS-Dilithium: A digital signature algorithm designed to replace methods like RSA and ECDSA.

Conclusion

The Number Theoretic Transform is a cornerstone of modern cryptography, providing the speed and precision necessary to build the secure systems of tomorrow. While it operates deep under the hood, this elegant mathematical tool is what makes it possible to create cryptographic systems that are not only safe from today’s computers but also from the quantum threats of the future. It’s a perfect example of how abstract mathematics finds powerful, practical applications in securing our digital world.